From Katrina to Melissa: Reflections on An Adaptable and Transferable Mental Health Response to Natural Disasters

Hurricane Katrina — the second deadliest hurricane in US history — made landfall in New Orleans on August 29, 2005. Two days later the pumping system failed and the levee breached, plunging eighty percent of the city under water. In addition to the natural disaster, poor political and administrative leadership were blamed for 1800 preventable storm-related deaths. The Congressional report years later, ‘A Failure of Initiative’ noted that medical care and evacuations suffered from a lack of advance preparations and inadequate communications and coordination. Intuiting that no one was coming to save us in New Orleans, a majority Black city most notable for its African cultural retentions – the birthplace of Jazz and Bounce music, the best seasoned and tongue-titillating food in America, second-lines and dance traditions derived from the ancestors – IWES rose up from the waters and established itself as a leading authority on addressing the post-disaster mental health needs of youth in our city.

“...over the 10 years of screening youth ages 12-18 years old, we found elevated levels of PTSD and Depression up to three times the national rate and resembling the rates of veterans returning from the Iraq-Afghanistan war.”

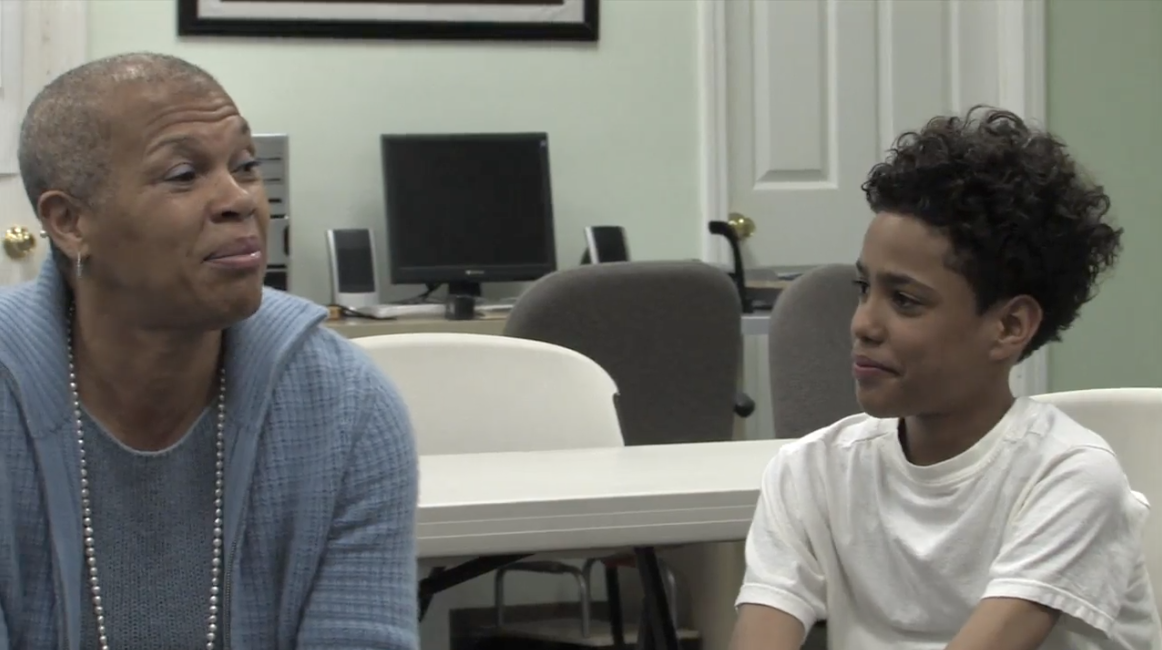

Screenshot from IWES footage post Hurricane Katrina

Why?

We were aware of the reality that climate disasters — an encounter between a hazardous force (hurricanes, flooding, fires, typhoons) and a human population in its way — create demands that exceed the coping capacity of the affected communities. And, in addition to the physical and environmental consequences, climate change disasters pose significant threats to the mental health of those impacted.

It was also evident that the existing health infrastructure, steeped in racial inequities, was poorly equipped to address the emerging impact of post-disaster trauma in already underserved populations. We knew that special attention and a people-centered approach should be used to address the needs of the more vulnerable sub-populations — women, children and youth, and pregnant women — but that didn’t happen right away (arguably ever) in New Orleans.

For children, in addition to the traumas associated with the disaster itself, family bonds can become broken and lead to further traumas related to attachment and separation. And for pregnant mothers, exposure to weather-related disasters could significantly increase stress hormones and impact the brain structure of their developing fetus, which could place these Katrina ‘in uterus’ babies at high risk for developing mental health disorders. Of note a study done of children born to mothers pregnant during Superstorm Sandy, found exactly that: in 2022, researchers(1) found those children had an increased risk for psychopathology - an over 5-fold increased risk for anxiety disorders, an over 16-fold increase in depression, and an over 3-fold increased risk for attention deficit/disruptive behavior disorders.

So, what did IWES do?

In the beginning years, having seen the literature on the link between lack of housing and the increased risk for developing PTSD, we promoted Housing First and adopted Dr. Mindy Fullilove’s Collective Recovery framework by creating communal spaces for community members to come together and:

tell stories;

learn about the impact of trauma on self and community;

learn calming techniques to manage stress like breathing, mindfulness, and body-scans;

access non-clinical wellness services like acupuncture, massages, and yoga;

reflect on heightened existential challenges such as isolation, freedom, life’s meaning, and death;

participate in rituals for renewal and revival;

re-envision the future; and

get screened for depression and PTSD.

In those immediate post-Katrina years while working in schools throughout New Orleans we anecdotally noticed increasing levels of dysregulation and aggressive behaviors amongst our youth, so we placed a special focus on supporting population-level youth mental health services. In 2012, we began 1) screening youth for PTSD and Depression, 2) conducting in-school psychoeducational lessons on stress, 3) providing teacher trainings on trauma-based mental health disorders in children, and 4) advocating for trauma-responsive and compassionate classrooms through our public-will campaign called In That Number (also known by its catchphrase “Sad Not Bad”). But these efforts were not enough to reduce the population-level impacts of such a devastating hurricane, and over the 10 years of screening youth ages 12-18 years old, we found elevated levels of PTSD and Depression up to 3x the national rate and resembling the rates of veterans returning from the Iraq-Afghanistan war.

What have we learned and what did we observe?

Indeed, New Orleans sunk into despair and uncertainty on August 29, 2005, and while there may have been moments of hope, it has taken a while to fully come back to the energy the city embodied prior to Katrina, especially with the demographic, housing, political, and economic shifts that have ensued. Those who have ever loved the New Orleans that was descended into existential despair. For some it was an acute stress disorder that lightened up over time with the hope of reconstruction and a brighter future; but, for a not-so small and significant number, the darkness never lifted and drifted from acute, to post, to persistent. For remember, fifteen years later came COVID, followed shortly thereafter by Hurricane Ida, which hit the city on the bittersweet sixteenth anniversary of Katrina’s initial landfall.

But while the city has experienced an emotional toll that few other populations in the US can comprehend, it is and always has been very resilient, and people have found their baseline as they define what their new normal looks like. It was from that baseline that we moved into this summer, the 20 year anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, ready to reflect on what happened, and dream of a healthier future that:

recognizes the significant impact climate change has had and will continue to have on the City unless adaptations are made to be more hurricane ready;

centers the arts, ancestral wisdom, and cultural practices and traditions as the main avenues to process trauma and grief and identify pathways to healing;

centers the needs and voices of our youth and provides them with reasons to hope and dream and expand their minds through exploration, deep questioning, and exposure to nature;

embraces diversity and rejects anti-Blackness, misogyny, LGBTQIA+ phobia, and xenophobia;

doesn’t criminalize those seeking survival; and

sees health, access to food, and housing as fundamental human rights that should be protected and provided to all.

To celebrate these ideals in action, in August, we joined forces with the city’s Katrina 20 Week of Action and commemorated the anniversary by going back to one of our earlier offerings for collective healing, Red Tents. We provided wellness services to any and everyone, free of charge, in a space perfumed by sage and incense and dedicated to ancestral reverence and calm. We provided sound baths, live soothing music, massages, herbal tinctures and teas, acupuncture, movement and dance, and the opportunity to pause and reflect at a reverential altar specially crafted each day.

Following the success of that event, we thought we’d arrived at a breakthrough and a moment to wind down some of our disaster recovery efforts — until October 28, 2025. On that day, Hurricane Melissa made landfall in Jamaica as a Category 5 hurricane and brought extreme damage, displacement, and flooding mostly to the Western Coast of the island, with wind gusts up to 285 miles per hour. Being Jamaican myself and having consistently connected our work to the island during our 30+ year history by bringing co-workers, program participants, and collaborators to Jamaica for workshops, retreats, trainings, and opportunities to advance our learning, we knew it was our time to rise up again! In early November we launched a new initiative, Rise Up Jamaica, to address the mental health recovery post-Melissa throughout the island. Our post-Katrina work taught us countless lessons around topics such as the role of partnerships and collaboration, narrative change, data collection & dissemination, and early strategic planning. Since New Orleans is now officially a Sister City to Kingston, we are even more committed to supporting the already robust mental health infrastructure in Jamaica and stepping up to help support not only those most impacted directly by the disaster, but also those who are tirelessly providing services such as doctors, nurses, social workers, and charity and aid workers. We encourage you to visit our Rise Up JA website and social media channels to learn more about what we’ve done in just a little over a month, and see if there are ways you can plug in and support, as well

As we move forward, what can we share with our Jamaican community still suffering from the acute shock of Hurricane Melissa?

We should name and frame severe weather disasters as the reality that they are — cataclysmic events suffered together as a collective trauma that shatters the foundation of our communities and elevates our sense of existential threat. Such angst brings us head-on and face-to-face with the givens of our existence: that as we are born so will we die; that we are born alone and will die alone and no one else can penetrate our conscious awareness of life; that we are born with no sign-posts and are ultimately responsible for writing the playbook of our lives; and that we have to discover and make meaning of our life, create our own sense of purpose.

As we heal, and within the deeper sense making of our existence, we also need to attend to our autobiographical dilemmas and conflicts, that which we inherit from our genes and our caregivers along the way. How do we know and attend to the feelings in our bodies, the thoughts in our minds, the actions that we take? How do we accompany the fear and guilt regarding our survival, and the grief of having lost those that we love? And ultimately, how do we risk our vulnerability and let our hearts break open, to allow the embers that broke our spirit transform into warm glows that fill our being with lightness and joy?

And finally, we experienced a collective trauma which in the end requires collective and communal healing. From drifting and dreaming in our spiritual spaces and places and being held with group meditation or prayers, to singing and dancing in the streets and at some point, laying a wreath for our ancestors for all the wisdom they gave so that we too could live and be resilient.

Find your way to process this trauma in community and in nature, because at the end of the day, to find true peace and healing, we must be one with all of the elements around us, the flora and the fauna.

“How do we risk our vulnerability and let our hearts break open, to allow the embers that broke our spirit transform into warm glows that fill our being with lightness and joy?”

REFERENCES:

1) Nomura et al. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2022; 0(0):1-12