Starting a family can be an exciting time for parents, but it also presents a variety of potential challenges. In order to thrive, many families benefit from comprehensive support and resources, including perinatal care, education, parenting assistance, and workforce training. These resources are often difficult to find, and existing programs tend to operate in silos, making it difficult for parents to access the resources they need over the course of their family’s development.

Such silos often include workforce agencies adding on socioeconomic services beyond their mission and capacities and parenting and perinatal organizations making referrals or informally coordinating with workforce agencies. Difficulties often involve parents handling multiple case managers, duplicate skill training, and extra effort of handling an uncoordinated journey through the silos.

To address this issue, a group of committed partners are developing a pilot program called the Perinatal, Parenting & Workforce Community Collaborative Initiative (CCI), an interconnecting pilot program being designed through a collaborative process Thanks to funding primarily from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the initiative was launched and is hosted by TrainingGrounds and facilitated by ResourceFull Consulting, with the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies (IWES) serving as the documentation and evaluation lead. Asante Salaam also supports the project as a Special Projects consultant, managing coordination and liaising between consultants, collaborating partners, and parents.

The CCI brings together 19 collaborative partners representing 14 organizations across the Greater New Orleans area, alongside five parent partners whose lived experiences and insights are central to shaping the program’s design and direction. The partners were represented by a designated Sector Lead role for the three sectors: Perinatal, Parenting, and Workforce. The program’s collaborative process was conducted through half-day group sessions held over the course of six months, and supplemented by surveys, one-on-one update or make-up meetings, interviews, focus groups, and Sector Lead design sessions.

The purpose of the design phase was to bring together parents and leaders from typically disconnected sectors – perinatal care, parenting, and workforce development – and create an environment where these individuals could sit down together and create a program that would allow families to seamlessly transition between services as their needs change over time. By recognizing the interconnectedness of parenting skills and workforce success, TrainingGrounds is offering a groundbreaking model that has the potential to make a lasting impact on the lives of young families. This report highlights the above-mentioned collaborative process and the experiences of both the organizational partners and the young parents.

“ I think if we stop seeing them as separate silos and separate program initiatives or goals, but see them as a collective group of goals, then we might actually have an opportunity to move the needle forward, not just on individuals but really in our city, move the needle forward.”

The Perinatal, Parenting, and Workforce Community Collaborative Initiative (CCI) is an ambitious vision to create a program that operates systematically to serve the families of New Orleans, Louisiana by uniting various sectors in an effort to streamline their work, and allow birthing people and their families a more seamless transition between the different stages of life.

OVERVIEW

To accomplish their vision, TrainingGrounds assembled a diverse coalition of stakeholders that consisted of their staff and leadership, representatives from organizations across New Orleans, and young parents aged 18-24. Also in attendance were Hamilton Simons-Jones and Maureen Joseph of ResourceFull Consulting, who facilitated the meetings, and staff from the Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies’ Research & Evaluation and Communications teams, who were present to visually document and evaluate the process. The CCI met monthly over the course of six months — from November 2024 to April 2025 — for approximately 3-4 hours per session. Upon reflection, an additional, previously unplanned meeting was added in April to complete work on the program design. To ensure equitable participation — particularly for parents, educators, and service workers — TrainingGrounds provided financial compensation to partners directly impacted by the state’s early childhood systems who were not otherwise compensated for their engagement, such as parents, child care providers, doulas, and community health workers.

The COLLABORATIVE

Throughout all of the meetings, members of the CCI were passionately engaged and were able to show up in the space as their authentic selves. The Collaborative benefited from an intergenerational group of attendees, and the majority of the CCI’s members were Black women, however men and individuals of other racial backgrounds participated, as well. Three Black men participated in the CCI, although one of them was not able to attend all of the meetings. Another of the three male attendees is an organizational leader at TrainingGrounds, Andre Apparicio. Although Andre was not included as a “parent” in the space, he openly brought his experience as a father to the group. To hear more about what this process was like for Andre and why he joined, click on the link below.

PARENT PARTICIPATION

Parents were engaged at the outset of the process as collaborators alongside organizational partners. Outreach for parent recruitment was conducted through two of the workforce partners, with a focus on parents whose lived experiences aligned with the CCI’s overarching goals. Ultimately, five parents formally joined the CCI, while several others participated in a dedicated focus group for parents to further inform the design process. The five parents that attended consisted of three mothers and two fathers, and they brought a wealth of experience into the space. To reduce barriers to participation, the facilitators were also committed to ensuring that both the parents and their families were welcome in the space; one mother and one father were a couple; another mother was expecting; and the parents frequently brought their children to the meetings.

ORGANIZATION LEADER PARTICIPATION

Partner organizations also demonstrated a high level of commitment and engagement during the meetings, even those that were unable to attend the meetings directly. One leader designated a senior staff member with deep expertise in relevant program areas. Similarly, another leader delegated three program leaders from their organization, all with aligned expertise, and also sent their associate director to contribute meaningfully during a key design session. Importantly, both of the aforementioned leaders remained engaged through one-on-one check-ins, offering valuable feedback and contributing resources. This proactive leadership and intentional delegation stands in contrast to more common committee dynamics, where program staff often join without executive backing, resulting in slower decision-making, reduced productivity, and limited resource alignment. This approach significantly strengthened the collaborative process and advanced shared goals.

Structure of the meetings

Meetings were primarily held at TraningGrounds’ site at the Sojourner Truth Center, except for the January meeting, which was held nearby at the local Head Start office. Both sites are in centrally located areas of New Orleans and near to a greenway and bike path and numerous bus routes, allowing for ample transportation options for attendees. For inclusivity purposes, the meeting space was arranged with tables in a “U” shape and seating was unassigned, yet participants often organized themselves according to their professional roles. Food was provided at each meeting, with a thoughtfully curated menu featuring a balanced mix of culturally appropriate options and nutritious choices. At the beginning of each meeting while participants settled in and ate, the ResourceFull Consulting facilitation team would share introductory slides with information such as the collective’s purpose, that month’s meeting agenda and objectives, the group’s community agreements, and the group’s overall progress. By opening up every meeting in this way, the facilitators set up an intentional, structured, and flexible tone for collaboration.

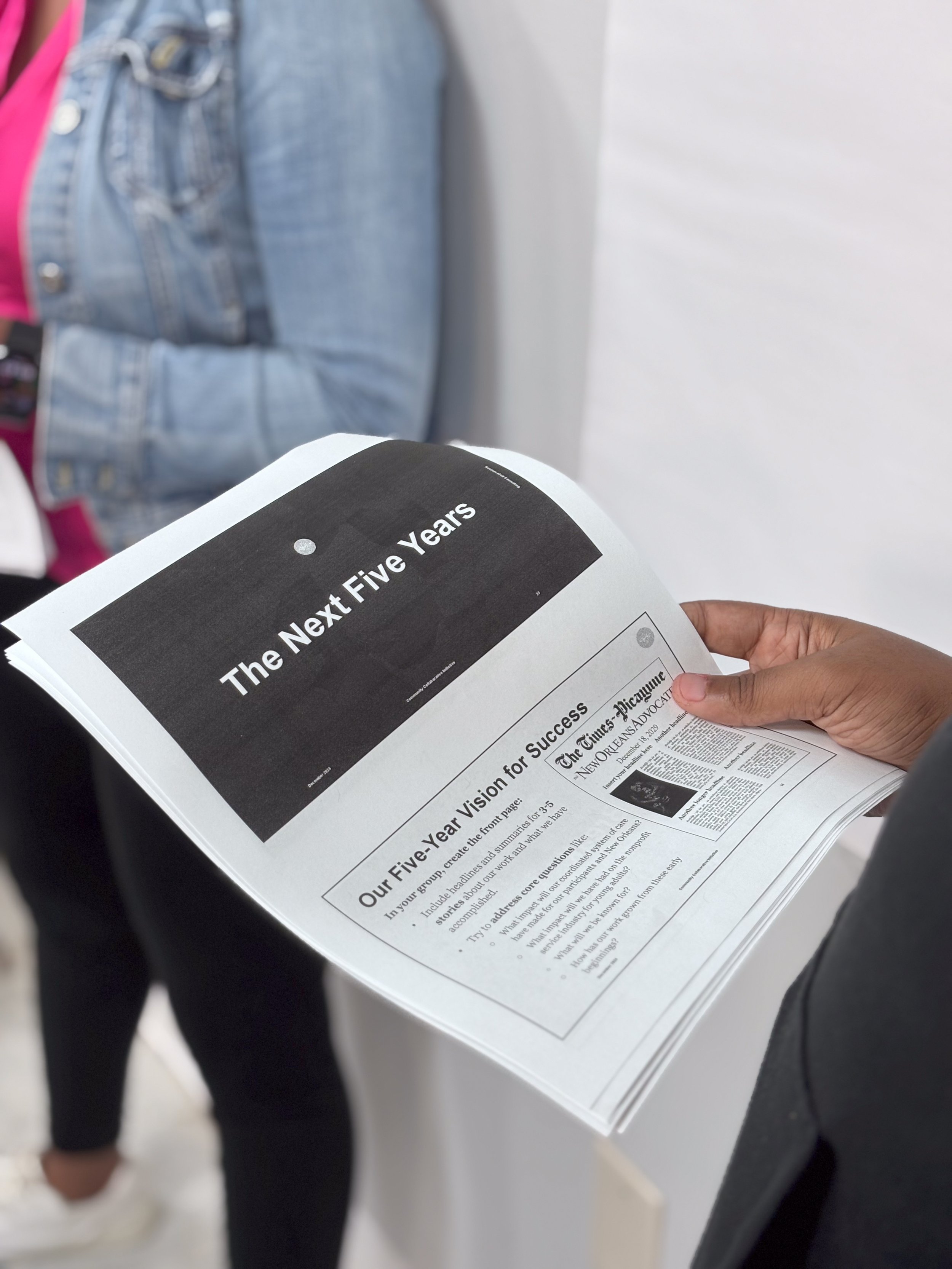

During the meetings, the facilitators used several strategies (i.e. small group discussions, large group discussions, consensus via voting, creative activities, etc.) and tools to engage participants through multiple mediums and formats and get them moving throughout the space. This process helped participants feel engaged and included, no matter their backgrounds, as it allowed for information to be shared, reflected upon, and processed through various learning modalities, and it allowed attendees to participate in a variety of ways. These strategies also promoted inclusivity and ensured that the decisions that were made took into account the expertise from both the organizational leads and the parents. Over the course of the meetings, the group discussed the values they shared and their dream and vision for the program. The meeting dynamic was representative of community trust, wherein all entities had a baseline level of trust for TrainingGrounds, which in turn enabled the members of the collective to quickly trust each other.

DOCUMENTATION

IWES staff were present to document the collaborative process as it unfolded. This consisted of photographing participants, taking notes, and conducting short interviews with participants to capture their feedback. Since the meetings were full of conversations and activities to engage participants, to avoid interrupting the work IWES staff pulled participants out of the room during pauses in the discussions. They were asked what they enjoyed about the activities, any challenges they faced, and what they hoped to accomplish. Interview participants were chosen based on their role in the CCI – whether as organizational representatives or parents – with the goal of ensuring a balanced representation of experiences. The interviews were transcribed by IWES staff and analyzed along with the observations the evaluators made and the notes they took for themes and major takeaways, which you will see included throughout the rest of this document. Excerpts from the videos and quotes are also linked throughout the document where relevant, and to watch all videos, follow this link.

Though many of the organizational representatives had experience working in other collaboratives, there were multiple unique components of the CCI which created an environment that fostered group decision-making.

Strengths of the Collaborative

Decision-Makers: The majority of organizational representatives in the CCI were executive-level leaders. In addition to their many years of experience and knowledge, they came to the table with the capacity to create impactful change. Their input and contributions are critical in ensuring long-term impact.

Consistent Attendance: Regardless of their role in the CCI, members were present consistently across all six meetings, notably at the aforementioned additional meeting in April. When it became apparent that additional time would be needed to finalize the program plan, CCI members were willing to convene for an extra meeting to ensure completion of the project. The meetings averaged at least three hours, which required dedication and focus from CCI members and showed the attendees’ strong commitment to the process, as organizational leaders are not often able to spend that much time out of the office and parents also often have many other competing demands. Rare absences were addressed through one-on-ones with lead facilitators and updates from Sector Leads to keep everyone informed of the planning process This level of sustained participation and engagement demonstrates that participants were fully aware of the importance of this work.

Mitigation Of Barriers To Access: As previously mentioned, some attendees were provided compensation for their attendance. This compensation reflects TrainingGrounds’ commitment to equity and the value they place on the lived experiences of parents and providers by removing financial and other related barriers to their participation.

Diversity In Expertise: Members of the Collaborative were intentionally selected and invited to the space to provide insight on the essential areas of expertise that would be necessary to design an effective system of interventions of this nature. Insight was needed from people not only with direct experience managing and designing these systems (such as staff and administrators), but also from those that interact with the systems (such as the parents), as well, to reflect upon what works and the previous challenges or barriers they have faced to accessing services or receiving consistent, sustained services over time.

Parent Participants: The consistent involvement of young parents from the communities the CCI aims to support benefited not only their families in real-time (participants were compensated for their time, effort, and expertise), but also enhanced the programmatic design by including voices that are often overlooked in the planning process.

Trust-Building & Pre-Existing Relationships: While not all of the organizations work together regularly, many of them already had an established relationship with TrainingGrounds. The trust that the organizations had in TrainingGrounds facilitated the trust that they were able to establish among each other.

Flexible Childcare: In alignment with their mission and core beliefs as an organization, TrainingGrounds provided flexible childcare options for parents. Beyond allowing parents to bring their children to meetings and hold them while they participated, this also included TrainingGrounds staff and other attendees offering to hold children for parents, providing on-site childcare in a separate space, and being flexible when parents stepped out with their children.

Nourishment: TrainingGrounds provided a thoughtfully curated selection of culturally appropriate and nutritious foods and refreshments at each meeting. The food was warmly received by participants throughout the meetings.

Facilitation Variety: The variety of strategies and tools employed by the facilitation team encouraged collaboration, provided many creative outlets for brainstorming and exploration, optimized comfort, and effectively brought the group to consensus in decision-making

COLLABORATIVE DYNAMICS

While participants generally respected and valued each other’s perspectives, subtle imbalances related to factors like age, race, professional role, gender, and pre-existing relationships influenced how participants engaged in the space. Such group dynamics can present themselves in any space with such a diverse group of participants, and the facilitators were very intentional in taking steps to mitigate these hierarchies. For example, the facilitators made purposeful efforts to center parent voice and lived experience, integrating parents into breakout groups, and encouraging participation. Despite these efforts, some of the barriers were still experienced in subtle ways and may have impacted how comfortable certain participants — particularly parents — felt to fully express themselves. That said, due to the CCI’s structure and the facilitators’ awareness of these dynamics, there is great potential for the Collaborative to overcome these barriers and create an even more inclusive space. Regardless of these minor differences, participants were still able to engage in many rich and fruitful discussions and many themes emerged throughout this process that are helpful for the CCI as it envisions future programming.

Structural Challenges for Young Families

During impromptu interviews and group discussions, parent participants shared many of the structural challenges they experience to successfully accessing resources and navigating systems of support. By raising these issues, this allowed the CCI to collectively brainstorm solutions to these barriers, and several of these concerns were addressed in the program design activities.

“I know a lot of young parents out there — mainly a lot of males — don’t really know in situations what to do, stuff like this. Because we don’t really have a lot of fatherly advice or like a father figure in our life.”

Lack of community due to societal economic shifts: Parents discussed that their family and community networks were less able to provide childcare compared to previous generations. The group discussed how grandparents – who were traditionally able to help with childcare – now face more pressure to work in order to afford the high cost of living. This shift in the responsibility for childcare from a shared role to an individual role has forced young parents to rely more heavily on social programming and resources for support instead of their families and broader communities.

Lack of information for fathers: As previously mentioned, two of the participants were fathers, and one of the young men, Vincent Lucky, noted that many young dads seldom receive guidance on fatherhood, often because they lack a father figure to turn to for support. He also discussed how parenting information was only catered to mothers while fathers were rarely given instructions on how to take care of their children. To hear more about Vincent’s views on this issue, click on the link below.

Lack of information on birthing rights: Many families and parents experience challenges even before a child is born, particularly when navigating the healthcare environment during labor and delivery. One parent discussed wanting more information on her rights as a person giving birth, including what she was required to consent to versus what she had the right to refuse and request.

Ineffective service delivery: Families often encounter fragmented services that rarely share information or align their efforts to collaboratively serve families seeking support. Participants shared that even when resources did exist, those resources did not always effectively reach the people who needed them the most, thus rendering the resources virtually nonexistent to those in need. A participant mentioned the need for stronger support from local, state, and federal agencies to close some of the service gaps across sectors.

Economic challenges: In addition to unemployment, many families experience underemployment – working in a job that doesn’t fully utilize their skills or that underpays. When one or both parents experience underemployment, it makes it difficult for them to meet their household’s needs. Participants noted how families are expected to survive when even those who are working may still be unable to afford to fulfill their household’s needs. This discussion was important to the design of the program, as originally only participants who were unemployed would be eligible for participation. This qualifier led the group to discuss the prevalence of underemployment and change the qualifications of future programming so that both unemployed and underemployed parents could participate.

“I want to see strong parents parenting their children, but I also know that if you have a premature baby, then that’s going to add stress, and if you’re stressed, then you’re not going to be the best version of a parent. If your work is not providing you with a livable income, then that’s not going to allow you to be able to be the best parent that you want to be. So for me, those were the kind of outcomes I wanted. I wanted young families to be able to have healthy births, I wanted them to be able to be really nurturing and active parents, and I wanted them to have income that could really sustain their families.”

“When we go to like doctors appointments and stuff like that, you mainly hear them talk to the mother a lot about situations or problems. They don’t really talk to the father about like, how to do, or what to do to take of the child type situations.”

As previously mentioned, participants generally respected and valued each other’s perspectives. The facilitators implemented several strategies to ensure that all participants, regardless of their background, felt like they could contribute to the space. These thoughtful efforts helped to create a collaborative atmosphere, however, it is extremely challenging to eliminate all barriers, and subtle group dynamics that are common to a diverse collective — around factors such as age, race, professional role, gender, and pre-existing relationships — influenced how participants engaged in the space.

Barriers to Collaboration

Dynamics between parents and organizations: The parents were recruited to the coalition through CCI partner organizations with which they already had previous relationships. While this reflects the positive impact those organizations have had on the young people’s lives, since many of the parents reported admiring and looking up to the organizational leaders, this dynamic may have made some parents hesitant to openly disagree with organizational leaders or offer differing viewpoints during sessions.

Dynamics between parents and organizational leads: There were a few instances where the organizational leads would – seemingly unintentionally – overshadow parents’ voices, particularly regarding the landscape of existing services. By the nature of their careers, the leaders generally have more technical knowledge of the network of available services within their sectors, but they do not necessarily have a parent’s perspective on how easily accessible those services are. Sometimes parents’ opinions on the landscape of available services was negated and “corrected,” and this may have contributed to their hesitancy in speaking about their experiences from their perspectives.

Language accessibility: While parents did not explicitly raise concerns about the language being used, the evaluation team noticed that parents seemed to engage less when technical jargon was used by other participants.

Logistical Challenges

As with any deeply collaborative initiative, the CCI process encountered a few challenges, which were addressed with proactive strategies:

Participation: One major partner organization initially offered a verbal commitment but did not follow through with participation in the session series, creating a gap in expected contributions. However, the partner received all meeting invites and follow-up materials, and never asked to be removed from the project or the partner list. The partner attended a virtual supplemental partners’ meeting held for final review and feedback on the group's collaborative pilot program design and implementation plan. Furthermore, the partner actively participated in the meeting and proposed valuable resources for the pilot implementation phase, thus demonstrating the importance of consistent engagement.

Barriers for Young Parents: One parent missed a meeting due to last-minute transportation challenges, while another was unable to continue participating due to their incarceration following the meeting they attended, an unfortunate reality that many of the young parents that this programming will reach have to deal with, whether personally, or through the impact of a loved one's incarceration. Both situations underscore some of the systemic barriers and vulnerabilities that many young parents in the Greater New Orleans area navigate regularly. The Project Manager coordinated communication with the parent participants and family members in both situations, enacting strategies which helped cultivate the relationships and maintain engagement despite the challenges.

Project Manager: Managing a multi-stakeholder initiative of this scale requires extensive coordination across consultant teams, partner organizations, and parent participants. This included logistical planning, regular communications, administrative oversight, financial management, and consistent relationship engagement.

Participants overwhelmingly shared positive experiences with TrainingGrounds and the Collaborative during their interviews.

Parents’ perspectives

Parents generally wanted more access to resources, information, and education related to being a parent, balancing parenthood with self-care, being pregnant and giving birth, how pregnancy and birth impact the body, and coping skills. They mentioned it would be especially helpful if a centralized hub of resources could be created which included what resources are available, where to find them, and how to access them.

One parent, Romeka Dickerson, mentioned that including a provider (e.g. pediatrician) in the space to provide their thoughts on this type of programming would have been helpful and meaningful.

“Only thing I feel like would’ve been missing is...’cause we have doulas, but a practitioner as well would’ve been great because they’re kind of two different people and it like, gives them a little bit more information that a doula would not give. ”

Reasons for participating

Several participants, both parents and organization representatives, provided their reasons for wanting to participate in this program.

“Being a young mom, and a first time mom, you don’t have a lot of people to talk to, so I wanted to join the group to see if I could get advice and learning skills from other mothers or other people who have kids.”

- Miesha Taylor, Parent

“A need is identified in the community and it’s bringing together different workgroups based on that idea that if we work together we could address the need.”

- Meshawn Siddiq, H.E.R. Institute

“...show that I’m engaged with my community as best as possible. Also ensuring that my skillset is utilized in a way that makes sense not only for me professionally but those who are around me as well.”

- Shannon Brown joseph, Workforce Collaborative Consulting

Thoughts on next steps

CCI participants mentioned looking forward to long-term, tangible outcomes and skills that young parents could actually use in practice, specifically the attainment of new competences and educational opportunities that could help youth develop long-term, sustainable careers rather than short-term employment. Across sectors and organizations, attendees wanted to ensure that the work they contributed throughout the six meetings lived beyond the shared space and actually made a difference for young parents in New Orleans.

“I’m hoping that, in our last meeting, with this particular phase, that we have developed a program that is not only strong but sustainable. Something that can absolutely impact these young parents and more than that.”

“...Not working toward the next steps, that we’re doing the next steps. All the plans come together and we move into whatever the next phase. It’s not just a pretty binder on the shelf.”

Participants’ thoughts on what could be improved

Participants reported few challenges and areas for improvement and noted that this was a very positive experience. Nonetheless, the reflections below were shared during interviews as two areas of improvement, and potential recommendations to consider for future endeavors.

Many participants stated they could have benefited from additional development and planning time.

Most participants agreed that recruiting more parents would be ideal.

Evaluation Team Recommendations

Upon reviewing all of the team’s notes, observations, and interviews, IWES’ Research and Evaluation Team has concluded the following recommendations on the process. The CCI may consider:

Mitigating Age & Career-Based Power Dynamics: Facilitators and sector leads should take into account and acknowledge the close relationships that youth may have with community-based organizations, and organization leads in particular. Since the relationships that parents had with organizational leads may have been a hindrance to open communication, explicit acknowledgement of this dynamic and creating space to talk through how to mitigate it may allow for parents and organizational leads to build a new base of trust and create a space where honest, open communication can flourish.

Centering Parents’ Voices: In addition to having sectors for perinatal care, parenting education, and workforce development, it may be helpful to create an additional sector for parents specifically and appoint a sector lead that is one of the young parents themselves. This would allow them to use their collective power to advocate for their concerns rather than just being a part of groups led by organizational representatives.

Accessibility: Strategically engage parents for feedback on materials that are created by industry professionals and extensively utilize jargon after they are shared to learn what was not clear and receive recommendations on how to make them more accessible for their peers.

Preparation for Young Parents: Provide an orientation to the parents participating in the Collaborative that includes verbal and/or written explanations of common technical or industry terms they may hear and a map that illustrates the landscape of available resources. This would also be a good time to engage in team building activities among the parents, which may further increase their network of support.

Thank you for taking the time to read through this report on TrainingGrounds’ Perinatal, Parenting & Workforce Community Collaborative Initiative (CCI). To hear more from the CCI members that were interviewed, yet whose quotes were not included in the document above, please follow the links below. If you have questions about the Evaluation report, please contact IWES at info@iwesnola.org. For more about TrainingGrounds or the CCI process, click on their logo below.

Andre Apparicio, Dad-A-Port

Angela Shiloh Cryer, STRIVE New Orleans

Arlanda Williams, Delgado Community College

Arnel Cosey, Clover

Azeb Negasi, Clover

Caitlin Scanlan, Cafe Reconcile

Dominique Garner Brewer, Total Community Action

Jahné Osby, Total Community Action

Lauren Jones, Parent

Matt Scott, Parent

Melanie Richardson, TrainingGrounds (Parenting Education Sector Lead)

Meshawn Siddiq, H.E.R. Institute

Michele Seymour, New Orleans Youth Alliance

Miesha Taylor, Parent

Rochelle Wilcox, For Providers By Providers & Wilcox Academy of Early Learning

Romeka Dickerson, Parent

Shanika Valcour-LeDuff, Labor and Love (Perinatal Health Sector Lead)

Shannon Brown Joseph, Workforce Collaborative Consulting (Workforce Sector Lead)

Sidney Monroe, Total Community Action

Sunae Villavaso, New Orleans Office of Workforce Development

Taeshaun Walters, Changing Generations

Thelma French, Total Community Action

Vincent Lucky, Parent

Project Manager:

Asante Salaam, TrainingGrounds

Facilitators:

Hamilton Simons-Jones, ResourceFull Consulting

Maureen Joseph, ResourceFull Consulting

Evaluation & Documentation:

Amber Domingue, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Ayesha Umrigar, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Iman Shervington, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Kimberly Garb, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Lisa Richardson, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Mari Jarreau, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Mary Rockwell, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Tyla Maiden, Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies

Founded in 1993, the Institute of Women & Ethnic Studies (IWES) is a national non-profit health organization domiciled in New Orleans, Louisiana. IWES is dedicated to improving the mental, physical, and spiritual health and quality of life for women, their families, and communities of color, particularly among marginalized populations, using community-engaged research, programs, training, and advocacy.

TrainingGrounds hired IWES as consultants on this project to 1) document the collaborative process; 2) create media content; 3) facilitate evaluation activities; and 4) provide comprehensive reports on the evaluation process that incorporate graphic and media elements. To achieve these goals, between 2-4 IWES staff members attended every session in order to take notes, record videos, photograph participants, and conduct short interviews on the process. Staff also met regularly with TrainingGrounds staff and consultants to check in on progress.

![TG CCI - [Session 4] --65.JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1744833714097-ILQV7BPH1OJ418XA06L8/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+4%5D+--65.JPG)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --09.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745855291047-FGGUGWMY8ZW2X4KAQXCY/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--09.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745855294081-010MRF70OD9VLYWYWKRM/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--11.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --03.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745855288091-ZPBCC4E638DTR3TWRRDC/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--03.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 4] --35.JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745894419363-LEIH08ELKA5WM7VI2G1D/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+4%5D+--35.JPG)

![TG CCI - [Session 4] --22.JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745889822942-PGDTPI35E0ALDG4BDPME/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+4%5D+--22.JPG)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --25.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745895431328-I84XEZYADBBQNLPO8BPE/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--25.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 2] --03-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745854674718-JS0M3UUR6627FSXR8DTB/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+2%5D+--03-2.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 2] --08-2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745854711554-HD7G5MITXZBOMBT792E2/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+2%5D+--08-2.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 2] --07.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745854700351-4YT4H5ZVJ4H2O082VU43/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+2%5D+--07.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 2] --15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745879429521-6IC6X0EJO2AV5PHOLKFU/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+2%5D+--15.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 4] --61.JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745894767188-570BBXO68LPC1NGZOE50/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+4%5D+--61.JPG)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --12.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745894024660-5WDJD75N3T234LM895OF/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--12.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --26.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745894700131-14AE8RIXRRCSKCTDIVTN/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--26.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 3] --19.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745895461884-VMC1QJ19N4A1RV3ICZGH/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+3%5D+--19.jpg)

![TG CCI - [Session 6] --13.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745895227661-WMUFFVTKEIP0H7B56NI5/TG+CCI+-+%5BSession+6%5D+--13.jpg)

![[Cafe+Reconcile]+Logo+Work+v4-01.png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59f78bfbf43b558afe23e48a/1745872799603-KXZK1MXZK4250HK4EY2J/%5BCafe%2BReconcile%5D%2BLogo%2BWork%2Bv4-01.png)